“I know that there are younger fans who are just getting into the album now,” founding Linkin Park member Mike Shinoda nonchalantly says of one of the best-selling albums of the 21st century. Initially viewed as one of the many “this too shall pass” nu-metal releases of its era, Hybrid Theory, released on October 24, 2000, became the best-selling album of 2001 in the U.S., achieved rare diamond status by 2005 (10 million albums sold), and has sold over 25 million copies worldwide since. It’s, in a word, a lot. Shinoda is also one of Linkin Park’s main songwriters; much of the Grammy-winning Hybrid Theory was born from him and his collaboration with his longtime bandmates, including late vocalist Chester Bennington. Shinoda remembers much of the process well, revisiting the work 20 years later.

The Hybrid Theory boxed set, out this month, includes the band’s original 2000 debut LP with the 2002 Reanimation remix album, the 1999 Hybrid Theory EP (from when the band still went by Hybrid Theory), and loads of B-sides, rarities, and demos, including the elusive “She Couldn’t” and “Pictureboard.” Even if you weren’t a fan then (or never became one), it’s fascinating to relisten to Hybrid Theory and realize that alternative and rock radio still lives and dies by the template perfected by Linkin Park. (Any legacy rock band would kill to have a YouTube video with billions of views — Linkin Park has two.) And in a post-emo rap world, Hybrid Theory sounds even more ahead of its time. In fact, critic Steven Hyden, in his great new book on Kid A, Radiohead’s seminal album that came out the same month as Hybrid Theory, makes the case that while Radiohead became obsessed with “evolving” rock music and bringing it to the future, Linkin Park were the future.

Below, Shinoda goes over all the highs and lows of 20 years of Linkin Park.

Biggest revelation from revisiting Hybrid Theory

We were younger than I remember. Theoretically, I know we were about 20, 21 years old. There’s a new DVD named Projekt Revolution 2002, and it’s all material that we shot at the time and never released — we were really young. Dave [Farrell] and Brad [Delson], in particular, you could tell they were college roommates. They had just come out of UCLA, having lived with one another for I don’t know how many years. I look at them and I feel like I’m looking at two roommates out of college.

Hybrid Theory track whose meaning has changed the most over the years

“In the End.” It’s such a weird one. The way the chorus came to me was in almost unabashed pessimism. If you listen to the lyrics, it’s so pessimistic, and I’m not really that pessimistic. Actually, my friends often accuse me of finding the silver lining in things too often. So to write those words and then have that be the biggest song off the album, it forced me to have a different perspective on what that song is for, and what the meaning of that song in the world is.

Basically, the songs were like an outreach. The songs were an invitation to the show, whether you listened to “One Step Closer” and said “That’s so dope — it’s so angry,” or if you listened to “In the End” and there was something about that pessimism and that negativity that you related to, you could come to our show. And it wasn’t a farce. That’s how I felt at the time. But in the big picture, that’s not who I am. So people would come to the shows because they connected with these negative emotions, and we gave them something positive to rally around. The songs were like, If you feel this way, come together. We always talked about a catharsis. They got to get out all these negative and difficult thoughts and emotions.

Hybrid Theory song you wish was a bigger hit

I’ve always said that “Papercut” was the track that defined Hybrid Theory for me. If there was going to be a calling card, that’s it. I knew that the other ones were better singles for all the reasons that they worked, but I always felt like “Papercut” was so much of the band in one song. It starts off with this really bouncy hip-hop beat. I was influenced by everyone from Jay-Z to Timbaland — Timbo a lot. That bounce, that beat in the beginning, it was probably part him and part the rock bands that were imitating that bounce, like ourselves. But the thing is, it starts out with this hip-hop bounce, then it immediately kicks in with a very at the time cutting-edge [version of] what you would now call a nu-metal riff. Over the top of that, if you listen, there’s a jungle beat, which is a subgenre of electronic music that never hit the mainstream. And then there’s the rap chorus, plus all the glitching effects on the vocal, and then you hit the end and it’s a huge melodic release. I think between the sounds, emotions, and lyrics, it’s very much [the direction of the] first couple Linkin Park albums.

But it was appropriately big — it was a single overseas — and people loved the song; it was the first song on the record. But if I could have made that the biggest song on the record instead of a role-player, then that would have been amazing.

Most memorable thing about Hybrid Theory coming out the same month as Radiohead’s Kid A

I remember being on the road and buying Kid A and listening to it. I think that we were in an RV at that time, or we were just getting into a bus. I remember sitting in New Orleans and it was raining, and we had just pulled into a hotel, and I didn’t go into the room. I think I was making a beat or something. We had an MPC that I brought into the bus and RV at the time, and I was listening to Kid A. I was such a huge fan of OK Computer, and I liked all their stuff up until that point. I got to Kid A, and I was like, Oh man, I don’t know about this. This is crazy. What are they doing? This is really avant-garde. Why are they going so far out there? And I say that as a fan of Nine Inch Nails, who would release these super abstract instrumental remixes of their stuff, and I bought all that stuff and loved it. Kid A was so far out there that it threw me off, yet over the course of the month, I totally fell in love with it. At the time of any of those things, you’re worried about perception, and I can’t imagine Radiohead ever saying anything about us.

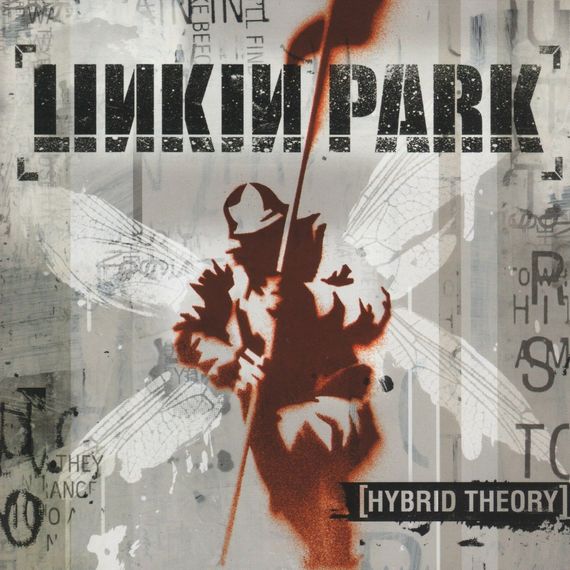

Linkin Park album covers, ranked

I’ll probably say Hybrid Theory for No. 1 — that icon of the soldier with the wings. It was the time when Banksy was brand new and people were just hearing about Obey and Shepard Fairey for the first time, and we just loved what would later become known as street art. We had seen the Banksy stuff in art publications like Juxtapoz. People were passing it around and stuff, and there was this image of this monkey that said “Laugh now, but one day we’ll be in charge.” It was the essence of Banksy — that sarcasm, political, and sociopolitical commentary. We also love the idea of stencil art. I made the soldier; Frank [Maddocks] stenciled and sprayed it. I didn’t come up with the idea for the wings. Somebody else, either Joe [Hahn] or Frank, suggested those, and then Frank kind of laid out the whole thing with the textures and everything. I don’t think I responded to the textures and the colors of it as much as I just responded to that stencil. The stencil on its own is a definitive piece of art for the band.

A strange choice, but I’d go with A Thousand Suns for No. 2. Then One More Light. The Hunting Party. What am I missing now? Living Things. Meteora. Wait, what am I missing? Which one am I missing? [Editor’s note: Gently reminds Shinoda of Minutes to Midnight, this writer’s first Linkin Park album.] What is the cover of Minutes? Yeah, Minutes to Midnight would be last. If you include the other remix albums, they would all fall lower than that.

Best-sounding Linkin Park song

Maybe I’m a little biased because it’s a newer song, but “Nobody Can Save Me” off of [2017’s] One More Light. I just grinded and grinded on making and layering it. It’s got so much to juggle. For 99 percent of its existence, it sounded good but not great. We pushed it all the way to mix, and I felt like, This is really good, but it needs to take a step up in the mix. I don’t know exactly what that means. We’re just going to hand it over. I ended up really pushing for [engineer] Serban Ghenea to mix it, because we’d never worked with him before but everybody knows his mixes. [Editor’s note: Ghenea has won Grammys for his work on Taylor Swift’s 1989, Adele’s 25, Bruno Mars’s 24K Magic, and more.] He’s incredible. He’s also got a certain, for better or worse, pop approach that is very direct in terms of the hierarchy of sounds. He separates sounds and organizes them really well. When he sent that first pass of the mix back, I couldn’t believe it was the same song. I was asking myself, Did he add or subtract sound? He probably turns down a lot of stuff. But he just made it sound so great. It was like, Oh, good, that last one percent is there.

Best-written Linkin Park song

This is like picking your favorite children. [But] “Waiting for the End” is easily a standout for me. That was very collaborative between me and Chester on the lyrics. I felt like I took the song to a place where I knew it was special, but I couldn’t crack the code, and then he walked in one day and we were just flipping through audio memos on his phone of things that he had just sung in the car or sung at home. And he played the verse from “Waiting for the End.” I was like, “Dude, that’s what this song needs.” We weren’t even listening to the memos in order to fix “Waiting for the End.” We were just listening to them to see what we should write that day. When it heard it, I very quickly realized that it would be the thing that the song was missing. Once we matched those two things up, it was one of my favorites. It’s still one of my favorite songs we’ve ever made.

[2010’s A Thousand Suns] had the most happy accidents. Sonically, I’m always looking for things that surprise me, that it’s almost like the type of thing that you listen back later and go, Wow, I can’t believe I made that. I don’t even know how I arrived at that idea. It’s such a unique thing to have happened. That album was full of those, partially because we spent a lot of time on it, so that allowed a lot of space for positive experiment.

Favorite Chester Bennington performance

I’m going to focus on the studio because live is really hard, just with the number of shows we played and the frequency with which he was so strong. He was just so great live. He had off nights just like anybody else, but his average show was spectacular.

In the studio, I’m going to probably side with our fans. One of our most notorious moments is this big scream on the bridge of “Given Up” [off 2007’s Minutes to Midnight]. I think it’s a 17- or 18-second-long scream. I had organized the song, and Chester hadn’t gotten familiar with the structure of the song when he was singing it. I had written a lot, or most of, those lyrics, I think, and he had just learned them; he was reading them off of a piece of paper. We got to the bridge, and he knew that he was supposed to scream “Put me out of my misery,” but he didn’t know how many measures that part was. So he just held the note as long as he possibly could. He was having a really good day in the studio. He had a ton of control, and he got to that point and just let it go well into the next chorus. I don’t remember exactly how far. And he’s like, “I don’t know how long just to scream that part.” I’m like, “Dude, I’m not touching that vocal. That was amazing. I’m just going to rearrange the song around what you just did.”

Best bad review

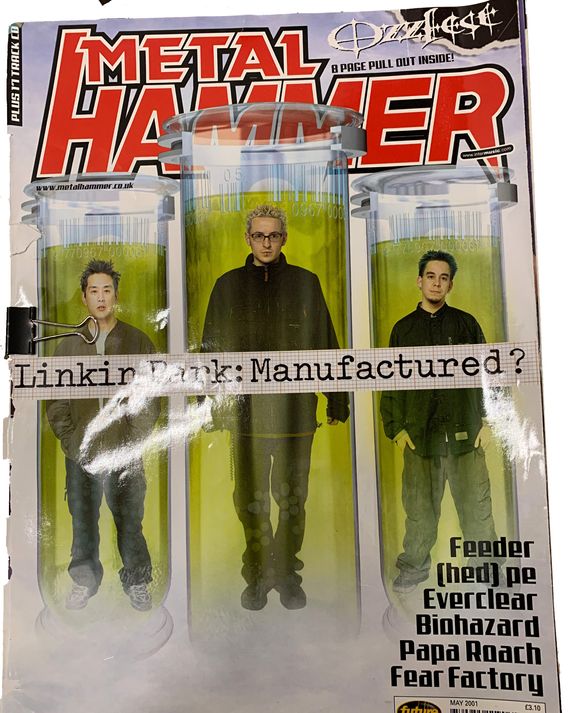

I immediately go to one that, at the time, was very well-known. These days, people have forgotten about it a bit. When Hybrid Theory really popped off, and around the time we released “Crawling,” we were months in on this album blowing up. The European press, but in particular the British press, was really nasty. I don’t know what was going on culturally at the time. They were so sarcastic and so manipulative and deceptive. They would come into an interview and start a question by saying “It’s been said that …,” and then they fill in that sentence with a lie or something they just made up that we had never heard. I can’t tell you how many times at that point we heard something for the very first time that somebody would present to us as a story or a rumor. At one point, I did say to somebody, “That’s not being said. You’re the only person that’s said that. We’ve done interviews every day, and I’ve never heard that thing you just said.” The one that stood out over them all was that we were manufactured by a record label who basically assembled us and wrote all our songs and just did a Milli Vanilli, or whatever, and put us together as a band and put out the album. That we were basically a version of ’N Sync, Backstreet Boys, New Kids on the Block, take your pick. I was really offended. I was pissed that that was going around. And all you can do is say “No” to that. “That’s not true.” And they’ll just go, “Yeah, right.”

Eventually, that really drove me on our second album, when we were writing Meteora. I was like, No. 1, we have to do it again, just to prove it to these people, because they’re watching us make it now. We can prove that we made the first one by making another one that’s just as good. Also, we have to film everything so that we can show the process and then they’ll understand that we’re sitting in the room, tearing our hair out to make these songs. It was great because, at the end of the day, that story did go away.

I’ll tell you the low point, which I can’t believe our publicist didn’t catch. We did a photo shoot for a magazine where they shot us individually on a green screen. And they were like, “Yeah, we’re gonna assemble you guys on the front cover, and you’re going to be the cover story.” I’m like, “Okay.” The issue came out. It was all of us superimposed in test tubes in reference to the manufactured band thing. That’s a huge jump from “We’re going to assemble you guys on the cover.” We didn’t know there was a concept involved, and nobody told us. They just did it, and the Photoshop was fucking terrible. We got it, and we immediately called management like, “What the hell happened? You guys didn’t know they were going to do this?” They were like, “No, and we’ve already called the magazine, but it’s out. They put it out. There’s nothing we could do.” Fans brought it to the show for us to sign, and we were like, “What is this?”

Most meaningful praise

When the lyrics or the music has helped somebody get through difficult times, that’s kind of what it’s for, you know? To connect with it in a way that is meaningful in their lives. It’s weird to think that in every meet and greet that we’ve had with fans, somebody says, “This song, this album — or your band — changed my life or saved my life,” and they don’t mean it metaphorically. They mean it literally, in some cases, because they’ll tell us the story about what happened. To have been listening to that statement for 20 years is insane. It’s totally insane. We’ve always tried to not become numb to that comment, to always respect that statement. We’ve always thought it’s important to not make a joke out of that.

It’s a very confusing thing when you hear something that’s that extreme so many times. We don’t take ourselves that seriously. I’m not a doctor. I’m not [physically] saving anybody’s life. Yet we’ve written some songs that people have found that much meaning in. It’s something we’re grateful for.

I always remind people: We didn’t want to be famous. We didn’t want to be popular for the sake of being popular. It’s a different time. Now people just want to be famous. I’m always so excited when I hear artists who are creating from a more pure place. If we got money, we spent it on music stuff every time. It was never like, “Oh, let’s buy fancy cars, outfits, jewelry.” Those things happened, but the intention was always to make good stuff that we thought was cool, that we thought our fans would like, or that would move the needle, be it culturally or technologically or artistically. Just things that we thought mattered. Even right now, I’m on Twitch five days a week just making shit. Somebody asked me, “Are you making good money on Twitch?” I’m like, “The Twitch channel doesn’t even pay for itself [laughs]. I’m just on there making shit.”

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.