The Napoleon You Never Knew

How one man's ambitions and intellect shaped world history.

How one man's ambitions and intellect shaped world history.

Table of Contents

ToggleNapoleon Bonaparte was transfixed with stories of ancient conquerors such as Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar. The young man who learned French as a second language would create a reputation as grand and lasting as his heroes of antiquity.

The young Napoleon rose from the son of a minor noble to an artillery expert to nearly the master of Europe. Through his military and civil reforms, in many ways, Napoleon helped to create the modern world.

Beyond what most people remember from high school, Napoleon shaped the wider world much more than most people would realize. The emperor created a number of systems that are still being used today.

Perhaps Napoleon is best known for his military genius. After joining the military at 16 years old, Napoleon voraciously read modern theory regarding artillery. His logistical skill and prodigious memory allowed him to make a name for himself in fighting between the French revolutionary government and a coalition of enemies in Italy.

From his success here, Napoleon was able to distinguish himself through a number of brilliant maneuvers. He prioritized speed in his military formations and was even able to surprise an Austrian army through his swift transit through central Europe.

“I have accomplished my object,” he said. “I have destroyed the Austrian army by simply marching.”

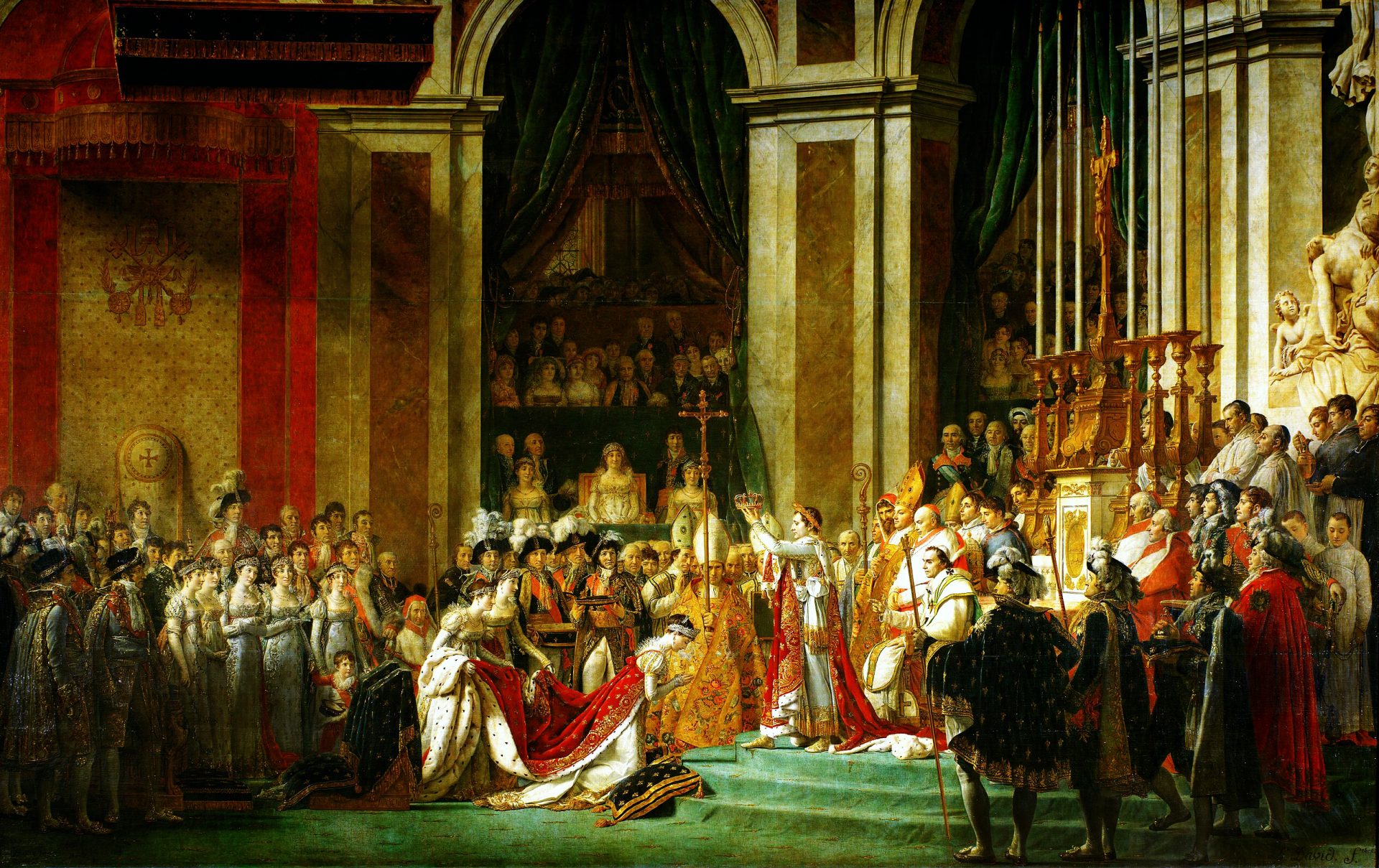

Napoleon’s genius could be seen in a number of battles, including smashing victories at Austerlitz and Marengo. His reputation and organizational skill allowed Napoleon to grow in political power, becoming the country’s dictator in 1799 and emperor in 1804.

He created the modern army corps system used by every major military in the world today. He fostered military innovation and prioritized merit among his lieutenants (although he was careful never to allow others to overshadow him.) But most people know that Napoleon revolutionized warfare. In many ways, his other innovations are the ones that left the deepest impact.

The changes made during the Napoleonic Empire had a major effect on the next two centuries of history. In part, it was direct. After Napoleon’s second exile in 1815, his family would rule France once more. Napoleon I’s nephew Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, became president of France after the Revolutions of 1848. The namesake of Napoleon would then overthrow the elected government and declare himself emperor, just as his uncle had been. Napoleon III in many ways modernized France, rebuilding much of Paris and expanding much of the country’s overseas empire.

However, Napoleon III is often better remembered for his blundering during the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871). The Emperor challenged the rising power of Prussia under the leadership of Chancellor Otto Von Bismarck and was forced from the throne after being captured in battle. Napoleon III also died in exile and his serious error regarding Prussia would play a major role in Germany’s rise.

Furthermore, the Napoleonic Code is still at the core of a number of legal systems across the world and not only in France. Many nations in Latin America utilize a modified version of Napoleon’s laws.

While the French Revolutionaries created the Metric System, it was Napoleon who standardized it throughout the empire and brought it outside of France’s borders (though he did try to revoke his decision later in his rule).

We also have modern canning thanks to the French emperor. Napoleon offered a cash prize to anyone able to preserve food for use on campaign. Nicolas François Appert created a system of sealing and sanitizing jars to preserve food, which became our modern canning.

Despite his larger-than-life reputation, Napoleon famously struggled with women and was involved with dozens of mistresses. Early in his military career, he is described as being awkward around women and almost sickeningly skinny.

The young general was originally engaged to Desiree Clary, whom he did not wed. Ironically, she would later marry Napoleon’s fellow general Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte. Napoleon would later name Bernadotte a Marshal. Following an interesting turn of events better suited for a full article, Bernadotte was named the crown prince (and later king) of Sweden. It was Bernadotte’s experience serving with and under Napoleon that helped him create the military strategy that would eventually defeat Napoleon in 1813 and 1814.

Napoleon instead married the widow Josephine de Beauharnais, a major socialite. The marriage was one which Napoleon seemed to take very seriously. Historians have found flowing love letters from the general during his time in Egypt to his new bride. However, at the same time, Josephine was carrying on a not-so-secret affair.

After Napoleon found out about his wife’s infidelity, he engaged in a large number of extramarital affairs, beginning during his time in Egypt. The exact number is not known, but a secret black book of the emperor detailing his affairs allowed for a better understanding of his mistresses. The book included records of a number of payments to his paramours.

This resulted in Napoleon having at least one confirmed illegitimate child. He affirmed one during his lifetime and DNA testing proved another from a Polish mistress. It is also likely that he had a number of other illegitimate progeny.

Napoleon seemed to have forgiven his wife for her infidelity and developed a deep and lasting friendship. Josephine was crowned Empress when Napoleon created the French Empire in 1804. However, the widow was also infertile and could not produce a legitimate heir for the emperor. Since he had at least one illegitimate child at the time, he knew that he was able to have children. He felt forced to divorce his wife, whom he considered his “lucky star” to marry an Austrian princess, Marie Louise.

Marie Louise was a marriage of convenience also meant to cement relations between Napoleon and a formerly hostile Austria. She strongly protested the betrothal but was soon won over by Napoleon’s charm. She gave birth to Napoleon’s son, nicknamed the King of Rome.

The Napoleon legend is closely tied to his time in exile. In 1812, Napoleon chose to invade his ally Russia, leading to a series of events that led to his downfall. Facing a string of defeats in 1813 and 1814, Napoleon saw his grand system fall apart. As he retreated across Europe back to France, his army was dwindling in size while Britain, Prussia, Russia, Spain, and Austria all aligned against him.

Napoleon was forced to abdicate by his Marshals after Paris surrendered to the Seventh Coalition. Facing no other choice, Napoleon surrendered to the allies. The victorious enemies placed the Bourbon Dynasty back on the throne under Louis XVIII.

In a compromise proposed by Russian Czar Alexander I, Napoleon was exiled to the island of Elba, off the coast of Italy. He was allowed to rule over the small island and kept the title of the “Emperor of Elba.” He was also joined by about 1,000 of his most loyal men. However, after 10 months on the island, Napoleon believed that he had an opportunity to return to power. Louis XVIII instituted a number of pay cuts and demobilization orders unpopular with the military. Meanwhile, the Coalition members were squabbling among themselves in Vienna.

Napoleon made his move in February 1815, arriving in southern France on March 1. Napoleon was joined by his followers and came home to a mixed welcome from the public. However, when the military saw their former emperor, it was a completely different story. One of Napoleon’s marshals, Michel Ney, told King Louis XVIII that he would bring him back in “an iron cage.” However, Ney and his forces soon joined the emperor.

In one story, Napoleon’s small band was approached by a French army regiment. Napoleon reportedly walked within firing range of the soldiers, opened his jacket, and said that if any man wished to shoot him, he was there. The soldiers soon joined their former emperor and his growing army.

Every army that Louis sent against Napoleon joined the former emperor. Soon, Louis saw what was happening and fled Paris. Napoleon entered the city and was soon acclaimed emperor a second time. However, Napoleon’s second reign nicknamed the “Hundred Days,” was not nearly as long or as successful as his first. The other nations of Europe named the emperor an outlaw and declared war on him personally.

Napoleon attempted to take the initiative and divide the allies. He won several initial battles in present-day Belgium but was ultimately defeated by a combination of a British and Prussian army at Waterloo.

After his second defeat, the allies were not going to keep Napoleon so close to Europe. This time, they banished him to one of the most remote islands on the planet, Saint Helena off the coast of Africa.

Napoleon would make no attempt to escape the island and would eventually die there at the age of 51 in 1821. During his time on the damp, uncomfortable island, Napoleon fought for his reputation. He dictated extensive memoirs and even wrote a book about Julius Caesar. Much of our modern perception of Napoleon is based on his writings during his second, and final, time in exile.

In many ways, Napoleon’s legacy overshadows the man. His legendary reputation on the battlefield, on the throne, and returning from exile means that he will forever remain a focus of fascination. If the upcoming Ridley Scott film about the emperor isn’t proof enough, Napoleon’s legacy will be linked to his thought that “Everything on earth is soon forgotten except the opinion we leave imprinted on history.”